Speaking Truth in Love

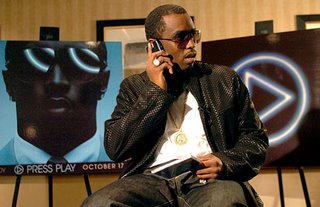

As an award winning writer, compelling public speaker, and ardent social activist, Kevin Powell continues to prick the conscious of American society with his latest book.

In the three essays that comprise Someday We’ll All Be Free the author candidly provides personal reflections on the volatile political and cultural climate of 21st century America. “Looking for America” addresses the Republican victory in the 2004 presidential election. “September 11th” offers Powell’s heart-felt laments in the wake of the horrific terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon. And a “Psalm for New Orleans” expresses Powell’s intellectual and spiritual insight on and physical response to the natural and unnatural disasters of Hurricane Katrina. But despite the individuality of topics and even literary style of the essays, there is a common theme that strings these poetically expressed pearls of wisdom together—Kevin Powell has a deep disdain for injustice and intolerance.

There are a few significant attributes of Someday worth note. First, Powell strikes the right balance between erudition and accessibility. Sure, the text is well-researched. Powell’s understanding of history is thorough and complex. And his political analysis is keen. For example, in the second essay the author engages the theme of terrorism from a historical and global perspective to decode the use of the term as a political power move and direct the reader’s attention toward those innocent victims --across ethnic lines—for which the term is not rhetoric but reality. Yet the author takes the reader from 19th century China, to 20th century Auschwitz, to 21st century Newark with a straightforward, rhythmic style of writing of which most professional academics, unfortunately, are incapable. Thus, Powell successfully addresses both ivory tower and armchair intellectuals in a clear and compelling manner.

Second, in contrast to the vast majority of the public/print discourse surrounding such highly-charged topics, Powell does not join the clamoring tongues of personal attack, visceral condemnation and performative displays of polemical grandstanding. Though an unabashed political leftist, Powell’s essays are self-reflective as opposed to accusatory and more concerned with fostering dialogue than playing the dozens. In the spirit of Martin Luther King, Jr. it appears that Powell does not desire to “wrestle against flesh and blood.” This is to say, no one particular person or group of people should be demonized as the enemy but all persons ought to raise a voice against and do what one can to alleviate human suffering. By distinguishing between a passion for true democracy and a milquetoast Democratic Party in American politics, in delineating patriotism from blind nationalism by holding the hawks of war accountable, and by disqualifying charity from the language of justice in seeking to rebuild the Gulf Coast region, Powell provides the sort of moral suasion that has proven effective at varying epochs in this nation’s history.

Finally, Powell’s reflections are morally clear and consistent. Powell’s vision of beloved community is not rooted in a utopian dream or a fool’s paradise. It is simply grounded in the wisdom of a 1st century Nazarene philosopher that taught us to “do unto others as you would do unto yourselves.” In this regard, unlike many in the hip-hop community, Powell resists a parochial black nationalism and a truncated heterosexism. The “all” in the title of this book means ALL. From the dispossessed black and brown youth of Brooklyn, to the gay suburban teenager, to the struggling farmer in middle America, simply put, “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice anywhere.” Thus, the author’s compassion looms large enough to cloak a vast cross section of humanity. This, in itself, makes the book a worthwhile read.

To be sure, there are a few aspects of this text that select readers might find off-putting. For instance, at times Powell’s rhythmic style of writing becomes overly repetitive. Rather than a lyrical genius in flow the prose reads more like a broken record. However, I am confident that these sections would sound much better pouring out of Powell’s mouth than they do when read from a page. Also, there are moments that Powell’s thoughts on the matters of presidential politics, 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina may appear somewhat fractious, borderline self-righteous and even an exercise of performed ululation. Powell’s constant professions of weeping, bouts of depression, vomiting, and overall blues tone of the essays weigh down the author’s buoyant spirit. This is not to say that a weeping prophet is an ineffective prophet. But the sense of hope that Powell teases out of his pain—which is readily transmitted in the author’s public lectures and addresses—gets enshrouded in Powell’s penned expressions of melancholy. Like a great balladeer, playwright or preacher that can take us down to lift us up, there are moments when the author leaves the reader in the valley of despair. To the extent that this is the case, the arduous task of descriptive writing, of which even the best writers must struggle, betrays Powell’s otherwise positivist spirit.

Yet overall Someday is an exemplary model of parrhesia. The author demonstrates moral courage, clarity and consistency to articulate his understanding of the truth from below. These insightful essays, then, force the reader to wrestle with our understanding of truth. In this regard, Powell has done a beautiful thing. For all we know it is the truth that just may set us free!

— 6 October 2006